This post is part of a living literature review on societal collapse. You can find an indexed archive here.

Reflecting about the end of our modern civilization requires counterfactual thinking, because fortunately it hasn’t happened yet. But this is not the only way counterfactuals help us understand collapse better. We can also create counterfactuals to reflect about past events. Not asking “Why did this happen?”, but “Why did not something else happen?” We can use counterfactuals to both explore the future, as well as the past. This post here is meant to provide some motivations on why we might do that, how we might do it and why it is especially helpful to think about large catastrophes.

Why and how to do counterfactuals

Before Philip Tetlock became well known for his work in forecasting, he also worked on counterfactual history. In the book “Unmaking the West” Tetlock and others try to come up with a variety of counterfactual histories which describe what might have stopped a few Central European nations from dominating much of the world history of the 19th and 20th century. Most relevant for us is the first chapter in the book which discusses common critiques of counterfactuals and how to make counterfactuals a more solid piece of scientific evidence (Tetlock et al., 2006).

The biggest advantage of using counterfactuals is that it helps us avoid hindsight bias. Usually, after an event has happened, this knowledge of it happening muddles our views. Before the event happens we acknowledge the uncertainty of the future and are able to entertain alternatives. However, as soon as an event happens this ambiguity collapses and our brains settle into the certainty of the present. Now it feels like “it had to happen that way”. But just because an event happened, it does not mean that it had to happen that way or even that the chance of it happening that way was high. It only feels like this because we ended up in the timeline where the event occurred (1). To avoid this bias, Tetlock advises us to use counterfactuals, as they bring us back to the mindstate we had before the event occurred.

A second argument by Tetlock is that we use counterfactual history in our everyday life either way, so we might as well just formalize it to use it for science. The idea here is that counterfactual reasoning is essential if we want to describe cause and effect. For example, if I say something like “the cat pushed the cup from the table”, I am asserting that the cat is the cause for the fall of the cup. To do so, I had to implicitly make the counterfactual claim that without the cat the cup would still be on the table. The same happens when we make claims about history. If I say “the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople destroyed the Byzantine Empire” I am making the counterfactual claim that without the conquest of Constantinople the Byzantine Empire would have endured. If we would not also have the counterfactual claim, we could only describe what has happened, but not link events in cause in effect. To stay with the example, we could say “the Ottomans conquered Constantinople” and “the Byzantine Empire was destroyed”, but we could not set them in relation to each other.

Tetlock therefore argues, if we are doing counterfactual reasoning implicitly anyway and it helps us to avoid hindsight bias, we should just do it explicitly so we can learn from it more directly. To do so he highlights the three main criticisms of counterfactual history and what has to be done to tackle them and thus produce resilient and reliable counterfactual history:

Counterfactual history is arbitrary

Claim: Using counterfactuals just opens up too many possibilities and deciding on which to follow up is just too random to be helpful.

Solution: Use the “minimal rewrite rule”. This means that you should aim for the slightest derivation from what has happened, which might help you with getting the insights you are interested in.

Counterfactual history is speculative

Claim: Counterfactuals are essentially fiction, because you can imagine whatever you want.

Solution: Ground your counterfactuals in as much historical background as possible. To do so, Tetlock advises to make sure that your counterfactual remains consistent with well established historical facts and statistical generalizations. You should also make sure that normal rules of cause and effect still apply.

Counterfactual history is self serving

Claim: Counterfactual histories are too easily influenced by the people writing it and always come to the conclusions they prefer.

Solution: Highlight who might take offense to your counterfactual and explain why you still think your choices are appropriate.

Following these rules, the book argues that the counterfactual histories they came up with allowed them to understand two important ideas about history:

Earlier events have a bigger impact on the overall trajectory than later events and historical trends become more irreversible over time

For example, it is easy to imagine how Europe never came to global power if you change some small event in 1500. It is almost impossible to find a reasonable event that you could change to stop Europe in 1800.

A better world is possible. Counterfactuals show that history has many branching points to either better or worse outcomes.

Storylines

Counterfactuals are not only helpful to think about the past, but can also provide us with insights for what might await us in the future. A commonly used approach here are so-called storylines. These were brought to prominence, especially in the climate change community, by Shepherd et al. (2018). Shepherd and co-authors start with the problem that climate change is often explored in a probabilistic manner. Meaning we employ lots of models and try to get an overview of all possible futures. While this is a helpful approach, it has some problems. Namely, if you are using many model runs or even many different models and only look at the aggregate results, it is likely that the most extreme scenarios will remain undetected, because they will be averaged out over the aggregated runs. However, they might actually be the events with the most expected damage, which you thus would have to prepare for.

To address this, they propose to use storylines. Here the idea is to focus on a single, plausible chain of events which might happen and explore this in depth. To select this chain of events it is often helpful to start with an event that has happened in the past and ask “What would have made this event more catastrophic?”. For example, consider a flood that has happened. A nearby town was spared the flooding, because the dam it was protected by remained stable. A storyline that could be spun up here is “What would have happened if the dam broke?” or “What would have happened if it had rained slightly more and the flood became higher than the dam?”.

It is important to note that storylines are not meant to make any probabilistic statement. It is more concerned with the question “Is this chain of events plausible and should we thus prepare for it?”. It is a useful framing, because science has shown again and again that humans have a hard time to grapple with probabilities. For example, behavioral psychology has established that many humans have a difficult time responding rationally to events that they themselves have not experienced. Essentially, we assess the probability of an event as less, if it is outside of our personal experience, even if we are given information about the true probability. This means it is very often the case that preparations are only done after the hazard has connected. Or to stay with the example, people only start to think about what kind of events destroyed the dam after it has happened. Storylines are meant to drag this process into the present and to make it feel more like something we have experienced. If we can show a plausible pathway, based on past events, how a large catastrophe might occur, we could have a higher chance to convince people to act now. To bring this point home Shepherd et al. highlight many examples of how this process brought results, where probabilistic modeling failed to convince stakeholders.

One of these examples is how storylines helped save the New York Subway from extensive damage. Storylines showed that the New York Subway had escaped major flooding only by a slim margin in the past. Therefore, the storylines constructed imagined what might happen if the tunnels get flooded. This showed that the electrical signal equipment would be damaged and would likely be hard to replace. Following this insight the Metropolitan Transit Authority adopted the policy that this equipment was removed when it was seen as likely that the tunnel might get flooded. This allowed the New York Subway to quickly resume transportation after flooding, what would otherwise have been a major setback.

A similar term for the storylines approach are so called “downward counterfactuals” which have been coined by Woo (2019). Here the idea is to go from bad historical outcomes and make them incrementally worse. Essentially asking the question: “How could this event have become X % worse?” and incrementally increase the percentage you ask for and see if you can still find a reasonable chain of events that could produce this worse outcome. This approach might be especially interesting for things like societal collapse and global catastrophic risk, as it could identify how the importance of different processes shifts as the size of the damage increases.

Using storylines can sometimes be a bit confusing, as people tend to understand quite different things under the term. Thankfully, a recent review by Baulenas et al. (2023) tries to clear up this confusion by highlighting the main ways people tend to use the term storylines. They identified three main ways:

Scenario-based storylines: These are qualitative descriptions of how the world might evolve. A typical example would be the IPCC’s Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. They describe the general idea of a potential future, which then can be integrated and modeled with climate models.

Physical climate storylines: This is the kind of storyline which is meant by Shepherd et al. as explained above.

Discourse-analytical storylines: This kind of analysis aims at capturing what is discussed in climate policy to understand the main narratives and metaphors.

As you see, these approaches are quite different. I think for societal collapse research, all of them could be helpful. I would love to read it if someone did the work to capture what the main narratives and metaphors around societal collapse are.

Baulenas et al. also recommend that we could combine these three approaches to create more useful storylines. For example, doing a physical climate storyline and then doing a workshop about it to try to find out what kind of narratives this sparks in the participants.

Global catastrophic risk and counterfactuals

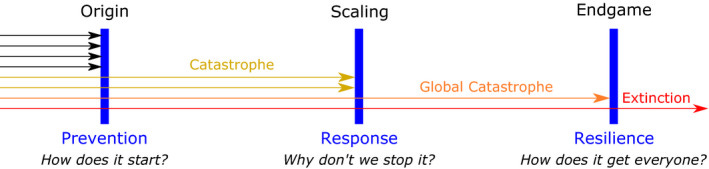

We now know that counterfactuals are useful to explore both the past and the future. One part of the future that this living literature review is often concerned with are global catastrophic risks. Here I think storylines would also be quite helpful as a way to counterfactually explore the future. While I have yet to see a direct storylines approach to global catastrophic risk, there is some usage of counterfactual thinking. One paper I want to highlight here is about the different layers of defense against global catastrophic risk by Cotton-Barratt et al. (2020). The idea is a bit more on the theoretical side, but they imagine the distinct steps that would have to happen for a catastrophe to potentially lead to the extinction of humanity (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Defense in depths against global catastrophic risk.

They imagine this to happen in three distinct steps, all of which could be used to halt the catastrophe in its tracks:

Prevention: The first way to stop a catastrophe is to prevent it entirely. This step is not available for all kinds of risks or only with unrealistic effort. For example, theoretically it is possible to prevent a supervolcanic eruption (2), but it is unlikely that we do so due to the gargantuan efforts. However, there are many catastrophes where we could decrease the likelihood of them even starting, e.g. we plausibly could stop climate change before it comes into the range of most tipping points (3).

Response: Many catastrophes start small and then escalate to larger to larger ones by processes like cascades. This means we also have the chance to intervene at this layer by stopping the catastrophe before it becomes large. An example here would be to identify an infectious disease early, before it has the chance to become a global pandemic.

Resilience: This assumes that the global catastrophe is already ongoing and now we have to cope with it. Here we can imagine something like a nuclear winter and how we can scale up a resilient food production (4).

Another example of global catastrophic risk and exploring future counterfactuals is the ParEvo process conducted at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk by Beard et al. (2023). The idea here is to explore a wide variety of futures by asking participants to build on each other’s ideas on what pathways the future might take. This happens by providing a seed text which outlines the general ideas and then let participants write short extensions to this text and extend ideas from the texts of others. While the result of this exercise all strayed too far into the hypothetical to be of immediate use, the idea has promise. Especially, if it would be combined with the ideas of Tetlock et al. on how to produce more solid counterfactuals.

Conclusion

Counterfactuals of both the past and the future can be a valuable tool for both global catastrophic risk and societal collapse research. In both cases very little research has happened yet. Especially, a storyline approach about a specific global catastrophic risk could produce much insight and also provide a plausible story which might help produce more policy engagement.

Thanks for reading! If you want to talk about this post or societal collapse in general, I’d be happy to have a chat. Just send me a mail to existential_crunch at posteo.de and we can schedule something.

Endnotes

(1) A recent example of this is the election of Donald Trump. Before the election pretty much everyone agreed that the election was too close to call and both candidates had a roughly equal chance of winning. Now that Donald Trump is elected, suddenly everybody has a crisp explanation on why it had to happen that way without any doubt.

(2) This is explored in detail in this paper.

(3) Here is the post that discusses tipping points.

(4) We discussed this in more detail in an earlier post.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, November 20). Counterfactual catastrophes. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/x3nr3-5v898

References

Baulenas, E., Versteeg, G., Terrado, M., Mindlin, J., & Bojovic, D. (2023). Assembling the climate story: Use of storyline approaches in climate-related science. Global Challenges, 7(7), 2200183. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.202200183

Beard, S., Cooke, N., Dryhurst, S., Cassidy, M., Gibbins, G., Gilgallon, G., Holt, B., Josefiina, I., Kemp, L., Tang, A., Weitzdörfer, J., Ingram, P., Sundaram, L., & Davies, R. (2023). Exploring Futures for the Science of Global Risk. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4405991

Cotton-Barratt, O., Daniel, M., & Sandberg, A. (2020). Defence in Depth Against Human Extinction: Prevention, Response, Resilience, and Why They All Matter. Global Policy, 11(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12786

Shepherd, T. G., Boyd, E., Calel, R. A., Chapman, S. C., Dessai, S., Dima-West, I. M., Fowler, H. J., James, R., Maraun, D., Martius, O., Senior, C. A., Sobel, A. H., Stainforth, D. A., Tett, S. F. B., Trenberth, K. E., van den Hurk, B. J. J. M., Watkins, N. W., Wilby, R. L., & Zenghelis, D. A. (2018). Storylines: An alternative approach to representing uncertainty in physical aspects of climate change. Climatic Change, 151(3), 555–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2317-9

Tetlock, P., Lebow, R. N., & Parker, N. G. (2006). Chapter 1. Counterfactual Thought Experiments: Why we can’t live without and how we must learn to live with them. In Unmaking the West: “What-If?” Scenarios That Rewrite World History. University of Michigan Press.

Woo, G. (2019). Downward Counterfactual Search for Extreme Events. Frontiers in Earth Science, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2019.00340