December 2024 Updates

Making sure this living literature review is actually alive

It has been a while since the last update post. Since then I have come across a lot of interesting papers and also changed some things around this blog here. I now keep both the Substack as well as the archive up to date, so you never have to wonder if you are reading the most recent version of a post. Due to popular demand (one person asked for it) I now also provide a list of all references used in the writing. So, if you are looking for the ultimate societal collapse reading list, this is probably it. Additionally, I now include a “Further Reading” section in the archive. This contains things I have written which I consider relevant for societal collapse, but which are not part of the living literature review itself.

If you enjoy my writing, I would very much appreciate it if you could share your favorite post with someone who you think might be interested in the topics discussed here. If you have a hard time deciding on what to share, here are the most popular posts:

And my personal favorites:

The universal Anthropocene (this post was published before the official transition to a living literature review, so most of you probably haven’t seen it yet).

Now the actual updates.

Trade collapse

Besides the production of food, distribution of it is another important factor. Same goes for other goods besides food. I explored what happens when this trade is disrupted or even collapses in this post. Since then I have published a preprint myself which also tackles this topic. Therefore, I updated the post to also take this paper into account:

How much of our trade could we potentially lose?

We therefore know that the food trade is quite vulnerable on many axes. But how would food security be influenced by changes in trade after a major catastrophe? This question is explored in Jehn et al. (2024) (Disclaimer: I am the main author in that paper). To do so, Jehn et al. used a simple network model of trade to simulate how changes in food production change food trade patterns. The assumption being, if you produce less food, you reduce your exports by the same amount. This approach allows to isolate the effect of the direct yield reduction, without having to make any further assumption on human behavior.

Jehn et al. used this model to look at the two main types of global catastrophic events that influence food production: 1) abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios (like nuclear winter), 2) global catastrophic infrastructure loss (GCIL, like a large geomagnetic storm disabling the global power grid) and 3) a combination of both (imagine a nuclear winter after a nuclear war which included HEMP attacks). They find that many countries would lose around 25-50 % of their food imports after a GCIL and 50-100 % in an ASRS. A combination of both would be even more disruptive.

Figure 2: Impact of global catastrophic infrastructure loss (GCIL), abrupt sunlight reduction scenario (ASRS) and a combination of both on food imports for all four major crops and all countries.

Besides these direct effects the paper also simulated how this would impact trade communities. A trade community is a group of countries which trade a lot with each other. They can change if for example one major exporter reduces its exports due to yield losses. Interestingly, the impacts here differ a lot by the catastrophe that caused them. In GCIL scenarios the trade communities stay mostly the same, because the food production is impacted relatively homogeneously. Meaning if most countries have a similar reduction in food production, your trading partners stay mostly the same. For ASRS scenarios though the picture is quite different. The climatic disruption caused by them is regionally quite different, completely destroying food production in some countries, while leaving others not impacted at all or even improving conditions in some (e.g. very hot countries). This completely changes the map of trading partners, as many countries would have to turn to new partners to have any chance of importing food.

All these things indicate that food trade would be massively disrupted after global catastrophes, with ASRS potentially being most disruptive.

In addition, I came across a recent paper “Vulnerabilities of the neoliberal global food system: The Russia–Ukraine War and COVID-19” by Yıldırım & Önen (2024). They provide another argument around the concentration in the food system which is also discussed in this post. I therefore, extended the argument in the section “Concentration on all levels”:

Another paper which links these problems in the food trade system to how global markets are structured is by Yıldırım & Önen (2024). They looked at which countries were most impacted by food system disruptions due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and COVID-19. They argue that this mostly impacted countries that have low income and which also do not have any domestic food production. They propose that these countries could impose import restrictions to strengthen their local food supply and make themselves less dependent on imports.

Anthropocene traps

My post about Anthropocene traps covers the idea that humanity has inadvertently built traps for itself, which decrease our resilience and make it more difficult to face challenges. I extended the discussion by a brief mention of the death spiral concept by Schippers et al. (2024):

A similar concept to those of anthropocene traps is the death spiral as introduced in Schippers et al. (2024). They define death spirals as “a vicious cycle of self-reinforcing dysfunctional behavior characterized by continuous flawed decision making, myopic single-minded focus on one (set of) solution(s), denial, distrust, micromanagement, dogmatic thinking and learned helplessness”. They think historically there are two main things that cause such a societal death spiral: 1) rising wealth inequality and 2) dwindling resources. In contrast to Søgaard Jørgensen et al. (2023) this more concrete problem identification, also provides a more concrete solution: reducing inequality to increase general societal resilience. This finding also fits with other arguments we have discussed on this blog. Especially, the research around democracies shows that decreasing wealth inequality is a very important factor to create a society resilient against catastrophes.

Climate anomalies and societal collapse

In this post I discussed the question if climate is the ultimate cause of societal collapse. I came to the conclusion that what actually matters is what kind of society is faced with a change in climate. I recently read “Navigating polycrisis: long-run socio-cultural factors shape response to changing climate”, which makes very similar points and so I used it to extend the conclusions a bit:

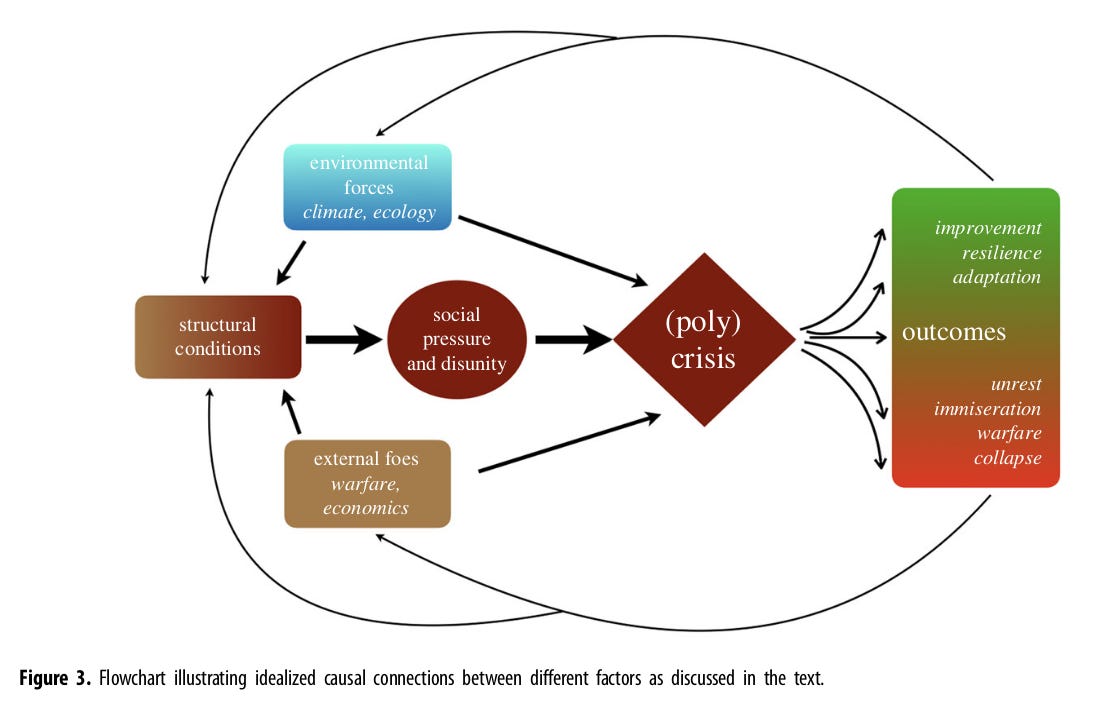

Another recent paper by the Seshat working group touches upon the question of what the actual mechanism is and how climate is involved (Hoyer et al., 2023). They make a deep dive into the Qing dynasty in China, the Ottoman Empire during the Little Ice Age and the Monte Albán settlement in Mexico to study the relationship between climate and society. They create a simple flowchart of how they think events play out there generally (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Flowchart showing how Hoyer et al. (2023) see the connection between climate and society.

The main idea here is similar to the other arguments made here. Climate is important, but it does not happen in a vacuum. If your society is making sure that the costs of extreme climate are fairly distributed through society and your resilience enhancing systems (e.g. irrigation in past societies or the electrical grid today) are in good shape, you have a good chance of weathering even big climate shocks. If your society is internally divided and skipped maintenance on its infrastructure, climate shocks can have devastating effects quickly. The vulnerability of your society is key to understanding the effects of climate.

Lessons from the past for our global civilization

How easily can we transfer insights from the past to today? I explored that question in this post. One important argument in the post was that we can see a similar trend of increasing complexity across different civilizations. Well, somebody else thought the same thing and published a whole paper about it: “The characteristic time scale of cultural evolution”. I have already discussed this paper in more detail in another post, but I wanted to add it in here as well, as it fits nicely into the overall argument.

This seemingly similarity in the scale up of different civilizations was also seen by others. Wand & Hoyer (2024) took a sample of 23 geographic regions from the Seshat dataset and tried to determine if all followed a similar pattern. They find that they indeed do so. Societies tend to need 2500 years to scale up their complexity from early settlements to premodern states. Finding such a clear pattern suggests that we might also find something like this if we look at the last 200 years. However, research here is still missing.

Participation, inclusion, democracy, and resilience

In this post I make the argument that inclusive and participatory societies tend to be more resilient. To also look at what makes a society less inclusive and participatory, I added a discussion of “Moral Collapse and State Failure: A View From the Past.”

Moral collapse and state failure

Another interesting point about the relation of participation and the stability of states is made by Blanton et al. (2020). Their idea is that an important factor for a society to stay strong and resilient is to have a shared moral code, which everyone adheres to. They argue that this allows more buy-in by citizens of a state, which in turn allows that state to prosper more as more collaboration is possible. To study this they apply a quantitative history approach and use a dataset of 30 premodern states. This dataset contains information about how good the government of that state was and then looked at how long these states lasted and how devastating their collapse was. They assessed the quality of the government by quantifying things like how fair the judiciary was, how fair the taxes were distributed or if the leadership had limits on its power.

Overall, they find that generally the higher the good government score of a state was, the higher the welfare of its citizens. Interestingly, they did not find any difference in the life span of states with good and bad governments. However, they did find that states with better government had a slightly elevated chance to face a more severe collapse if a collapse occurred. They explain this with the idea that if a state provides more goods to its citizens, these citizens build upon this foundation and become reliant on it. If this structure of the state breaks down, so does the higher welfare that the citizens have built upon it.

Based on a couple of case studies (Roman Empire, Venice, Mughal Empire and the Ming Dynasty) they also try to discern what usually made these states collapse. They think the causal mechanism here is that even states with good government tend to break down when the elites and leadership stop contributing their fair share to society. For example, if I clearly see that the leadership in my state is allowing and participating in corruption, this in turn makes it less appealing for me to contribute to that state, while also incentivizing me to also get corrupt and get a share of the riches by defecting.

Mapping out collapse research

This post started my living literature review and gives an overview of the different strands of collapse research. Originally, this post ended with the outlook that the working group around Daniel Hoyer might publish a paper that will give us new insights, by working with large scale historical datasets. By now this has been published as a preprint and I have discussed this in a post in much detail. To reflect this, I have rewritten the last few sentences of the collapse overview:

However, this is a long term project, which requires much more work. Still, it would be an important piece of work, as we need to understand how past collapse has worked, to be safe against the complex, intricate and possible unexpected ways our society might be in danger today. Something along those lines has been proposed by Hoyer (2022) and partially implemented in (Hoyer et al., 2024). I discuss this in another post in more detail, but the general gist is that it is difficult to attribute the survival of a society to a small number of factors. Still, if you had to choose the interplay of elite behavior, the state capacity and the size the external shock is probably a good place to start looking. This is obviously only a partial answer, but at least it provides a good place to start looking.

How long until recovery after collapse?

Here I tried to answer the question on how long societies might need to recover if we ever face a collapse. While I did not read any relevant papers here, one reader requested that it would be helpful to have some more explanations on what I see as the differences between the stages of development (thanks Aron), so I extended that explanation.

History suggests three main stages in the development of civilization from early human societies to a global civilization:

Hunter-gatherer to early agriculture/pastoralism. The main switch here is that humans become sedentary for the majority of the year. Imagine a small village with some huts and a few fields of crops around them.

Early agriculture/pastoralism to pre-industrial society. Here the development is towards a society like in medieval England. You have a clear state structure with a defined hierarchy, which controls vast swaths of land. Technology progresses, albeit slowly.

Pre-industrial to industrial society. The endpoint here is essentially the society we live in right now.

I have also rephrased the ending a bit to better highlight the uncertainty in the assessment:

However, you could also make the argument that many of the metals are actually easier available now, because we have already refined them and you just have to melt them again. Similarly, the ruins of the past civilizations might inspire humans to recreate today's achievements, or they might be seen as a cautionary tale, never to be repeated.

Overall, this leaves me a bit ambiguous when it comes to our chances of recovery from civilizational collapse. If we have not completely broken the Earth in the process of collapsing, I would guess that it seems likely that we will make it back to pre-industrial levels in a few thousand years. If we will make it further than that seems quite uncertain, as the environment will simply be quite different to our first attempt at building a global civilization.

Until next time

Thanks for reading! If you want to talk about this post or societal collapse in general, I’d be happy to have a chat. Just send me a mail to existential_crunch at posteo.de and we can schedule something.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, December 4). December 2024 Updates. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/dk9kw-caj16

References

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., & Fargher, L. F. (2020). Moral Collapse and State Failure: A View From the Past. Frontiers in Political Science, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2020.568704

Hoyer, D., Bennett, J. S., Reddish, J., Holder, S., Howard, R., Benam, M., Levine, J., Ludlow, F., Feinman, G., & Turchin, P. (2023). Navigating polycrisis: Long-run socio-cultural factors shape response to changing climate. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 378(1889), 20220402. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0402

Hoyer, D., Holder, S., Bennett, J. S., François, P., Whitehouse, H., Covey, A., Feinman, G., Korotayev, A., Vustiuzhanin, V., Preiser-Kapeller, J., Bard, K., Levine, J., Reddish, J., Orlandi, G., Ainsworth, R., & Turchin, P. (2024). All Crises are Unhappy in their Own Way: The role of societal instability in shaping the past. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/rk4gd

Jehn, F. U., Gajewski, Ł. G., Hedlund, J., Arnscheidt, C. W., Xia, L., Wunderling, N., & Denkenberger, D. (2024). Food trade disruption after global catastrophes. EarthArXiv. https://eartharxiv.org/repository/view/7339/

Schippers, M. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., & Luijks, M. W. J. (2024). Is society caught up in a Death Spiral? Modeling societal demise and its reversal. Frontiers in Sociology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2024.1194597

Wand, T., & Hoyer, D. (2024). The characteristic time scale of cultural evolution. PNAS Nexus, 3(2), pgae009. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae009

Yıldırım, C., & Önen, H. G. (2024). Vulnerabilities of the neoliberal global food system: The Russia–Ukraine War and COVID-19. Journal of Agrarian Change, n/a(n/a), e12601. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12601