In the last year nuclear winter was a topic I spent a lot of time on. It is one of the potential global catastrophes that motivates me in general and it is directly relevant to my work (Jehn, 2023; Jehn et al., 2023). This makes it kind of obvious that I take nuclear winter seriously. However, when talking about my work I heard push back like “interesting study you did there, too bad it is on a topic that is completely made up”. Such statements surprised me, as there is a lot of research in recent years that does global simulations to understand the effects and implications of nuclear winter (e.g. Coupe et al. (2019)). This work has mainly been done by the working group and colleagues of Alan Robock, a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Rutgers University.

Over time I realized that the criticism about nuclear winter can roughly be split in two camps. The first camp is about traditional academic debate: Scientists criticize other scientists, because they think they found flaws in the methods of others. In nuclear winter, the debate here mainly is about the question of how much soot would be delivered into the upper atmosphere. This depends on how well modern cities burn. We don’t really have data on this, so it makes sense that we are unsure. The team around Robock is known for often taking very pessimistic assumptions, so it also makes sense that people criticize him. If you want to read more about this discussion, Hess (2021) wrote a good summary.

The second camp I would classify as science skepticism. Some individuals hold alternative perspectives on nuclear winter, portraying it as a mostly discredited idea often associated with left-leaning, anti-war ideologies. Upon my initial encounter with this viewpoint, it struck me as similar to the debates surrounding climate change skepticism. People express vehement skepticism about the soundness of the scientific evidence, despite its credibility. I came across this position mainly in conversations and such, but a concrete example of that outlook would be this comment I received for a nuclear winter post I wrote:

“You should first check if nuclear winter is actually a thing. The first proponents from the 80's seem to me ideologically motivated and their theory was refuted in 1991 when soot from Kuwait's burning oilfields failed to stay at high altitude. Than [sic] around the year 2000 academics made even wilder claims that nuclear winter could be provoked by 100 nukes from an India-Pakistan war which is far less in numbers and more local than the tens of thousands of nukes used in an intercontinental bombardment presumed by 80's models. Science has problems being self correcting when it relates to ideologically important topics.“

This post is meant to explore the origins of the second view.

The origins of modern anti science tactics and ideas

First let us look into the deeper roots of science denial, before we focus on the specific case of nuclear winter. I want to discuss a great history of science paper by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway (2022). Their paper explores why science denial is such a big problem in the contemporary right. Interestingly, science denial in general can be traced back to the same place in time and even partly to the same people as the nuclear winter denial.

In his inaugural address Ronald Reagan said “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem”, and it seems he believed this wholeheartedly. This sentence summarizes nicely what neoliberalism is about. The idea is that free enterprise is the cornerstone of a free society. Every compromise to economic freedom is always a compromise to political freedom. Therefore, you have to keep the government as small as possible, to allow the maximal amount of economic and political freedom.

However, these ideas did not suddenly pop into existence when Reagan became president. Oreskes and Conway trace the origins of those ideas to the beginning of the 20th century.

1920s to 1930s: Electricity in the United States was not seen as part of the public infrastructure. If you wanted electricity you had to pay for it yourself. However, many people thought that electricity should be public infrastructure, available to everyone. Unsurprisingly, the private electricity companies were against this, as this would have destroyed their market. To make sure that electricity stays a private market, they launched a massive propaganda campaign. They hired academics, rewrote textbooks and developed curricula for business schools. The one big message they promoted was that private property is the foundation of the American way. Interfering in the business of private companies was therefore deeply unpatriotic. However, they ran into a problem. People mostly did not buy it, as they realized that having electricity provided by the state would actually be pretty good for them. A similar chain of events happened during the Great Depression, when the National Association of Manufacturers ran a large scale campaign to argue for the idea that the Great Depression had nothing to do with market speculation and banking failures, but was instead caused by unions, taxation and regulations.

1940s to 1970s: Ultimately, these campaigns failed. The United States continued to introduce more regulations. For example, the power grid in the United States came under governmental control in 1934. However, these campaigns helped considerably to bring the idea of the paramount importance of private property into the public debate in the United States. The biggest proponent of these ideas at the time was the University of Chicago, funded by private philanthropists. In these circles the idea arose that they needed something similar to “Das Kapital”, but for neoliberalism. They found their neoliberal Karl Marx version in Friedrich von Hayek, an Austrian neoliberal economist. They funded him to write a book, which resulted in the 1944 publication of “The Road to Serfdom”. This book is the source of the indivisibility thesis: The idea that any compromise on economic freedom threatens political freedom. The Road to Serfdom was a very academic text. To make it easier to understand, the University of Chicago funded the scientist Milton Friedman to write “Capitalism and Freedom”, which explained the indivisibility thesis in layman's terms ("The book appears on virtually every list of the top 100 or even the top 10 books by conservatives").

This work of over half a century of developing anti government ideas found its culmination in the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Reagan strongly believed in it and relied a lot on people like Friedman to form his government's policies. The biggest effect was on taxes. These decreased considerably during the Reagan government. While the government was in general for deregulation and smaller government. They were still very open to funding the military. The main part of the government that was getting more and more funding during his presidency was the military and especially the nuclear arm. However, Reagan had a problem. Scientists during that time started to find more and more results that the uncontrolled capitalism and nuclear build up were a danger to mankind.

The scientists were mainly concerned about three topics:

Nuclear winter

Environmental pollution

Climate change

For all three of these issues, they contended that robust government intervention is essential to safeguard our planet's habitability. However, this stance stood in stark contrast to the preferences of figures like Reagan and the proponents of neoliberalism. Their inclination leaned towards reduced government involvement rather than an increase. Nevertheless, scientists persisted in emphasizing the necessity of such intervention.

As their ideological standpoint clashed with empirical scientific findings, the Reagan government opted mostly to ignore scientific findings or even directly challenged them without an empirical basis to do so. They also withdrew funding from critical scientific endeavors and redirected resources towards researchers who were more inclined to publicly endorse perspectives aligned with government positions. Some examples of their shift from relying on scientific findings and instead only promote anti-regulatory measures:

Before Reagan took office, scientists linked air pollution to acid rain. The Carter administration was working on a pollution-limiting treaty with Canada. However, Reagan's administration shifted course, questioning the science and interfering in peer reviews. In 1984, George Keyworth, the presidential science advisor, influenced a review to make findings appear less certain, justifying inaction.

The previous government had provided the Environmental Protection Agency with additional funding and responsibilities to combat the environmental destruction in the United States. Reagan reversed those changes and installed a corporate lawyer as the new head of the agency, who strongly opposed regulations like the Clean Air Act.

The Department of Defense helped discredit nuclear winter as described in the next section.

Over time these tactics eroded the trust of the right wing and neoliberals in science in general, which leaves us in the unfortunate political situation we often find today.

How NATO defunded and discredited nuclear winter research

This section here is based on the work of Simone Turchetti (2021). Turchetti dug into the archives to find out why so little nuclear winter research and why people are so critical of the concept.

NATO is not only a military alliance. It also is a vehicle for diplomacy. It tries to make sure that its member states get along well. One way that was done extensively is by funding research projects, to bring together scientists from different countries. NATO was spending a lot of money on this. According to Turchetti, NATO was one of the biggest science funders in Western Europe in the 1960s and 1970s. Richard Nixon even thought about making NATO more than a military alliance. It should also research global environmental topics, as a way to unite NATO members behind a common goal.

This led to important research being funded by NATO. For example, the research by Paul Crutzen into the destruction of the ozone layer was originally funded by NATO. However, in the 1970s, the scientists who got funding from NATO got interested in a new topic: Global climatic changes. This not only included global warming, but also the potential climatic effects of a nuclear war. Leading voices here were Paul Crutzen again, but Carl Sagan pushed this topic into the public consciousness.

This set off some alarms at NATO. Such research directly called into question the whole existence of NATO’s nuclear posture. If the indirect effects of a nuclear war kill you, even if you would be able to deflect all incoming missiles, then the whole idea of having nuclear weapons is called into question. At the same time, Luis Alvarez and others discovered that an asteroid impact had killed the dinosaurs, giving further credibility that global, disruptive events could wipe out a species.

All this new science about nuclear winter hit exactly at the wrong time for NATO. This was directly during the euromissile crisis, where NATO wanted to deploy more nuclear capable missiles in Europe. This faced massive protests, especially after the idea of nuclear winter got widely publicized by the ABC broadcast “The Day After” and the BBC movie “Threads”.

So, the NATO officials had to find a way to convince the public that it was still okay to deploy more nuclear weapons. They somehow had to discredit the whole idea of nuclear winter. If nobody believed in it, they would have an easier time again to deploy nuclear capable missiles as they saw fit (1). The first step was easy. NATO was the biggest funder in this area. They could simply stop funding all nuclear winter research. For good measure they also stopped funding most of the climate change research, as they feared insights gained there could also be used to bring the nuclear winter research forward as well.

The second step was more difficult. They had to make sure that people thought nuclear winter is not a credible scientific idea. Here they used one of the classic tactics of science denial. Find some scientists who hold the views that align with yours and provide them with funding. Some examples include:

Gumundur Sigvaldason and Claude Allgre: Two volcanologists who argued that volcanoes never caused abrupt climatic changes in the past (2). Therefore, if volcanoes cannot shift climate rapidly, nuclear weapons can’t either.

Antonino Zichichi: He organized "independent" workshops on nuclear winter using NATO funding. He invited nuclear winter critical researchers like Edward Teller and gave them a platform where they could talk unopposed about the impossibility of nuclear winter, without having the need to do actual science in the area (3).

Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory: These organizations rejected all nuclear winter projections at the time. They even did some simulations on their own. However, at least to me it is very suspicious when an organization funded by the military comes up with conclusions which are exactly what the military wanted. Finding those two organizations here was also a bit of a surprise to me, as they are also the leading voices in nuclear winter criticism today. Seeing them here, further decreased my trust in their research today.

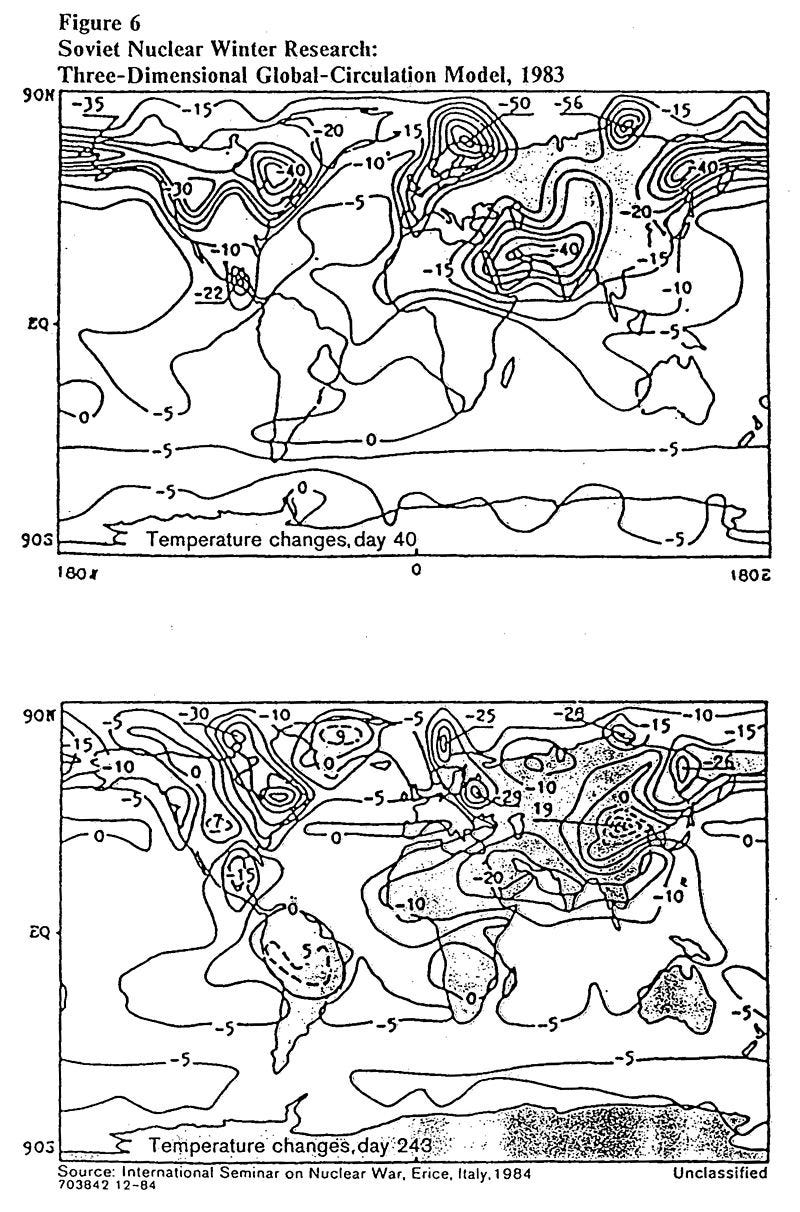

One additional piece that made it easier for NATO to discredit nuclear winter was that Soviet scientists believed that nuclear winter was a problem. Vladmir Aleksandrov did some studies that reconfirmed the original nuclear winter results. This was used as evidence that nuclear winter is actually a psy op by the Soviet Union and left leaning scientists in the USA (4).

Example of the Soviet nuclear winter simulations in the 1980s.

Unfortunately, this two pronged attack at nuclear winter research worked. People took the idea less seriously (5). Also, after the end of the Soviet Union, even the idea of a nuclear war itself faded away. This led to nuclear winter disappearing from the scientific debate almost completely for around three decades. Fortunately, this has started to change again in recent years.

Summary and Conclusion

The case I want to make is the following. The neoliberal politics of Ronald Reagan and others ran into the problem that their idea of a small government and avoidance of regulations conflicted with scientific findings about environmental destruction. They solved this by diverting funding away from those researchers that criticized them and towards those that had more aligned opinions. Over time this eroded the trust conservatives put into science, as their political leaders told them again and again things that conflicted with scientific findings. It also provided a playbook which was used in various instances. One of them is climate change (6) and another one is nuclear winter in the way described here. I think the science denial about nuclear winter I came across is rooted in those historic events.

It seems however, like nuclear winter becoming more of an openly discussed topic again. I am not sure what the exact reasons that it is moving more into the Overton Window, but here are some ideas:

Open Phil provided a good amount of funding to recreate the nuclear winter research from the 80s, but with modern climate models (Robock et al., 2023). This gave new credence to the idea.

Nuclear war is not the only kind of event that can lead to an abrupt reduction of sunlight. Large volcanic eruptions can have the same effect. We now understand the mechanisms better and this can be partly transferred to nuclear winter.

A range of very big forest fires have shown a similar mechanism in soot uplifting as we think might happen after a nuclear war (Damany-Pearce et al., 2022).

Movements like Effective Altruism have brought global catastrophic risks more into the public debate again in general.

The world situation in recent years has been very volatile due to major disrupting events like the COVID pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This might have shown people that we have to consider catastrophes more.

I hope that this time nuclear winter will stay on our agenda and not fade back into oblivion again.

Endnotes

Turchetti refers here to official NATO protocols as the source. I do not have direct access to those, so I cannot independently verify it. Please also note that I am summarizing Turchetti’s points. All this is explained in more depth in the original paper.

Which is wrong, but I am not sure what the science said at the time, so they might have done this in good faith.

Edward Teller is widely recognized as a very ambivalent figure when it comes to his views on the possible uses of nuclear weapons and their effects on the environment. See for example, his wikipedia article or Turchetti’s book “Greening the Alliance”, which contains a multitude of comments about Teller (Turchetti, 2018).

Which might really have been the case. However, I can find sources that claim that the Soviets were surely using it as a psy op and others that say that the idea of nuclear winter was one strong reason the Soviets wanted to end the cold war. Therefore, I am not sure what to make of that point. See Scouras et al. (2023) for some discussions around this topic.

Turchetti mentions that it decreased a lot on how much this was discussed in the public, but does not cite specific numbers.

I can strongly recommend the book “Merchants of Doubt” if you want to dig deeper into climate change denial (Oreskes & Conway, 2012).

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2023, September 28). Science denial and nuclear winter. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/f3ew7-etr74

References

Coupe, J., Bardeen, C. G., Robock, A., & Toon, O. B. (2019). Nuclear Winter Responses to Nuclear War Between the United States and Russia in the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model Version 4 and the Goddard Institute for Space Studies ModelE. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 124(15), 8522–8543. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030509

Damany-Pearce, L., Johnson, B., Wells, A., Osborne, M., Allan, J., Belcher, C., Jones, A., & Haywood, J. (2022). Australian wildfires cause the largest stratospheric warming since Pinatubo and extends the lifetime of the Antarctic ozone hole. Scientific Reports, 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15794-3

Hess, G. D. (2021). The Impact of a Regional Nuclear Conflict between India and Pakistan: Two Views. Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 4(sup1), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2021.1882772

Jehn, F. U. (2023). Anthropocene Under Dark Skies: The Compounding Effects of Nuclear Winter and Overstepped Planetary Boundaries. Intersections, Reinforcements, Cascades: The Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Stanford Existential Risks Conference, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.25740/ZB109MZ2513

Jehn, F. U., Dingal, F. J., Mill, A., Harrison, C. S., Ilin, E., Roleda, M. Y., James, S. C., & Denkenberger, D. C. (2023). Seaweed as a resilient food solution after a nuclear war. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7615254

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. (2022). From Anti-Government to Anti-Science: Why Conservatives Have Turned Against Science. Daedalus, 151, 98–123. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01946

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2012). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming (Paperback. ed). Bloomsbury.

Robock, A., Xia, L., Harrison, C., Coupe, J., Toon, O., & Bardeen, C. (2023). Opinion: How Nuclear Winter has Saved the World, So Far. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2022-852

Scouras, J., Ice, L., & Proper, M. (2023). Nuclear Winter, Nuclear Strategy, Nuclear Risk. Defense Technical Information Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1201181

Turchetti, S. (2018). Greening the Alliance: The Diplomacy of NATO’s Science and Environmental Initiatives. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/G/bo31043377.html

Turchetti, S. (2021). Trading Global Catastrophes: NATO’s Science Diplomacy and Nuclear Winter. Journal of Contemporary History, 56(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009421993915