Strong democracies are a necessity for crisis management

Why crisis governance depends on democratic capacity

This post here was written in collaboration with the Geopolitical Insight and Education Foundation. It was originally published here. They are think tank focused on democratic stability. This post was improved with lots of ideas, comments and suggestions by Bennett Iorio and Sandro Sousa. Check out their work, they will post several additional pieces about democracy by other authors in their commentary program ‘Drivers of Instability & Effects on our Democracies’. I am cross-posting it here to this living literature review, as it summarizes nicely many of the arguments I have made about the advantages of democracy.

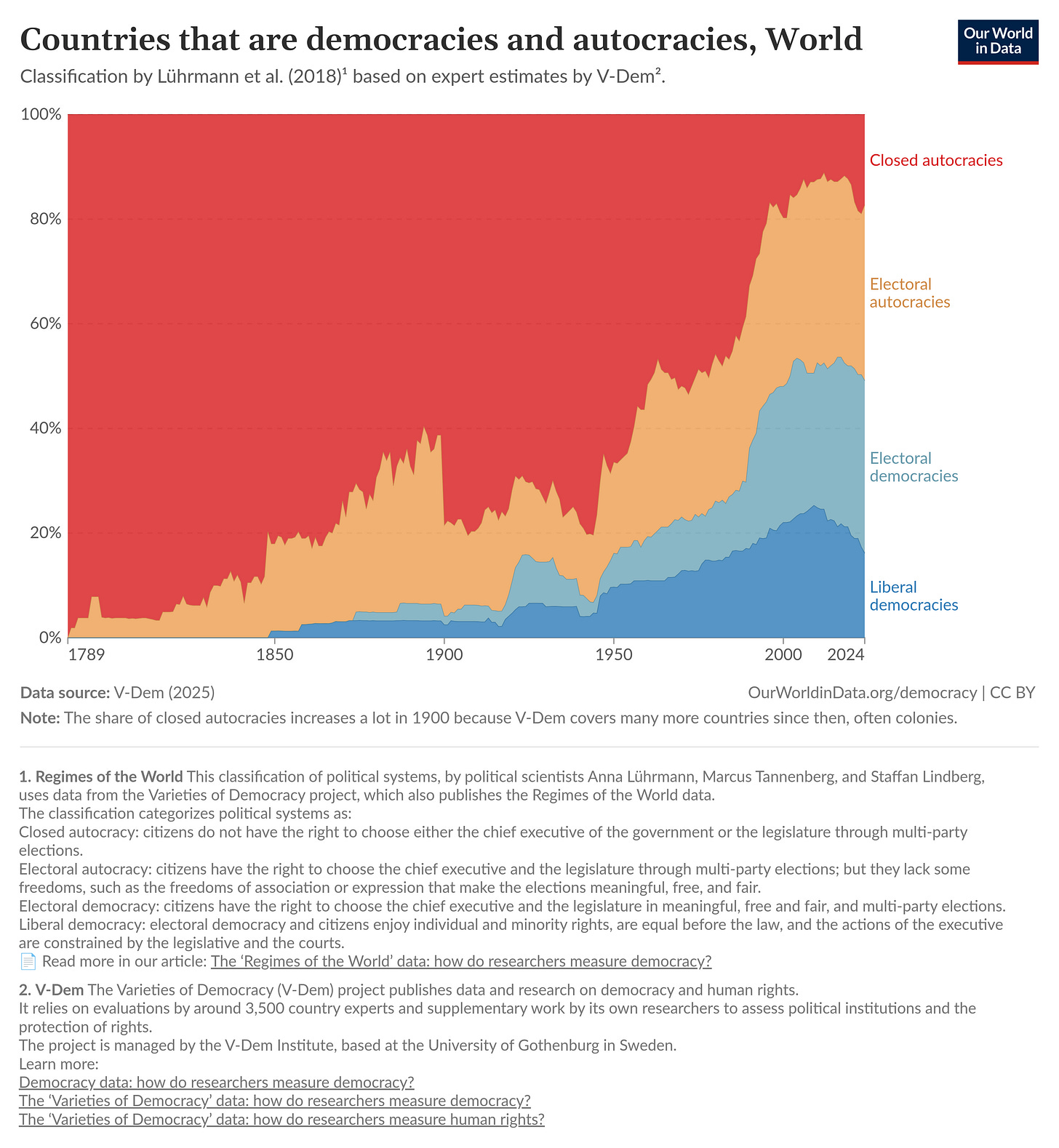

The proportion of the global population living under the spectrum of political systems classed as a democracy is near its all-time high, and stands (very approximately) around 4 billion, or around half of the global population. From a historical perspective, democracies have had quite the run over the last two centuries: Before the revolutions of 1848, 0% of the global population lived in what we would today recognize as a democracy, as none of the existing states satisfied various essential democratic properties like truly accountable leadership, as well as free and fair multiparty elections (Lührmann et al., 2018; Our World in Data, 2025), though the 100 years preceding the 1848 revolutions saw significant progress in this direction in Europe and the new United States. Since 1848, democracies have seen a meteoric rise, reaching their high water mark around 2010. However, progress has stalled and since 2010, the proportion of population living under democratic rule has decreased (Figure 1). Some of this may relate to demographic trends, with aging populations and decreasing overall percent of population in “traditional” democratic heartland territory like Europe, North America and Japan as compared to significant population growth in the global south, often in countries with democratic deficits. As a pointed example, the world’s fastest growing country, Niger, is also ranked amongst the lowest in terms of democracy and freedom.

Figure 1: Proportion of global population living democracies or autocracies (1789 to 2025). This figure should be read with the caveat that democracy is not a binary category but a spectrum, and regime classifications inevitably simplify complex institutional realities.

But the main and more dire driver of this change is the erosion of democratic standards and ‘backsliding’ in many democratic polities. ‘Democratic’ status in countries that in 2010 were still flawed or even full democracies, like Hungary, Slovakia, India and Russia, is now under threat, with many now being classed as ‘electoral autocracies’. Put simply, democracy as a system has proven highly resilient in the preceding two hundred years, growing its population share enormously, but not fundamentally invulnerable to reversal.

This is quite concerning on many levels; first and foremost because democracies are the only form of government where leaders can be held truly accountable and the population is a stakeholder in government, not only a subset of powerful citizens. There is ample evidence too that democracy as a ‘self-correcting mechanism’, that is, a system with robust checks and balances has been a significant factor in the staying power of democratic systems (Aspen Institute, 2017). But there is a second order reason that democracies should be protected and nourished, not only for their own sake, but on a systemically important level: They are more effective than other governance systems at both preventing and managing disasters and catastrophes. So, protecting democracies is not only a moral imperative for our societal wellbeing, it’s also necessary to avoid destruction, collapse and human harm after large catastrophes.

Why democracies are better in crisis management and prevention

Historical evidence

As stated above, democracies in their modern definition have only existed since 1848, so issues of correlation (with other major historical trends, such as industrialization, colonialism and decolonization, etc.) present a statistical problem for how we understand and disentangle the cause and effect of disaster mitigation, and we cannot easily look into deep history to understand how democracies face threats. However, democracies have certain features that define them and which can also be found in pre-democratic societies. This means when we look into history, we can sample societies that score high on these democratic values and use them as a proxy for how democracies might have fared under those circumstances, and draw conclusions on the impact of these proto-democratic mechanisms and their impact on societal resilience.

An approach like this was implemented in two studies by Peter Peregrine (Peregrine, 2018, 2021). In the first study Peregrine collected data from 33 societies which faced a total of 22 catastrophic climate disasters (mostly drought). The idea of the study was to test whether greater local participation and more community coordination/governance, or high enforcement of societal norms more effectively increase resilience of societies against catastrophe. To track this, Peregrine coded variables, including how steep hierarchies were, and how much social norms were enforced (e.g. by looking how much rituals and dwellings were standardized). This resulted in an overall score of how much social norms were enforced and how steep hierarchies were. These scores were then compared against societal outcomes (change in population, health, etc.). The study’s result demonstrated that societies with stricter enforcement of norms (a proxy for less democracy) had poorer outcomes than less hierarchical societies (a proxy for democracies), which tended to have better outcomes. A similar argument was made in the recently published book Goliath’s Curse (Kemp, 2025). In it Kemp, describes how lootable resources allow wealth accumulation, which leads to monopolized violence and enforced hierarchies. On a wide range of historical case studies, he shows that these enforced hierarchies are inherently unstable and that humans tend to prefer to live in more egalitarian societies.

Building on this, the second Peregrine study used a similar approach, but focussed on the Late Antique Little Ice Age (the coldest volcanic winter in the last 3000 years, and used by societal researchers as a rough proxy of a nuclear winter). Just as with the first study, Peregrine compared societal outcomes with markers of hierarchy and participation. And just as with the first study, more flexible, participatory societies fared better. A useful modern analogue can be found in contrasting democratic and authoritarian responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, which constituted a large-scale, exogenous stress test for state capacity, social compliance, and adaptive governance. China’s response relied on extreme centralization and coercive enforcement, including prolonged mass lockdowns, mobility controls and information suppression. While these measures initially reduced transmission, they generated significant second-order costs: Delayed detection of outbreaks, brittle compliance, economic dislocation, and ultimately a loss of global public trust, as well as destruction of trust in the state’s own policies within the country (Zhang et al., 2024). By contrast, countries such as Denmark adopted a markedly different approach, emphasizing transparency, decentralized implementation, and voluntary compliance grounded in high institutional trust. Denmark imposed relatively limited and time-bound restrictions, avoided prolonged school closures, and relied heavily on public communication and local discretion - yet achieved comparatively low excess mortality and faster social recovery (Mathieu et al., 2020). Importantly, this contrast should not be read as a simple function of regime type alone; demographic scale, urban density, and health-system structure are relevant too. Nevertheless, the comparison reinforces the historical pattern identified by Peregrine of a highly centralized, norm-enforcing systems appearing effective in the short term but tending towards brittleness under prolonged stress, whereas participatory systems with distributed authority and trust-based compliance exhibit greater adaptive resilience.

A much larger dataset, which captures all major polities of the last 5000 years shows similar results (Hoyer et al., 2025). This dataset measured crisis outcomes (e.g, French Revolution, Fragmentation of the Mughal Empire or Meiji Restoration in Japan) and how they relate to the properties of the involved polities. They find that one important factor if a state manages to introduce reforms to end a crisis is the hierarchical complexity. More concretely, they find that there needs to be a sufficiently complex state with a power base outside of the administrative apparatus of the state. Which is exactly what democracy is for; stable democracies trend away from highly centralized power structures, and instead rely on balancing power between institutions and interest groups.

There is also a companion paper to Hoyer et al. (2025). In this other paper, the aim was to understand what countries can do to prevent a crisis before it occurs (Hoyer et al., 2024). To understand they searched for cases of societies, which came right before the brink of crisis, but then successfully led to peace again. The four clearest cases for such a behavior they find are the conflict of the orders in the early Roman Republic (494-287 BCE), the Chartist movement in England (1819-1867), the reform period in the Russian Empire (1855-1881) and the Progressive Era in the USA (1914-1939). The critical element they shared to allow reform before the crisis became unmanageable was that they managed to generate enough elite buy-in and a broad societal alliance. This provided enough power to implement reforms against the special interests of powerful elites. Once again, this indicates that democracies are better at managing crises. Although it is also challenging to form broad alliances in a democracy and oppose vested interests, because of the central idea of decentralised power, it is still likely to be more effective at managing such issues than other forms of government.

Modern evidence

The Peregrine studies provide compelling evidence that more participatory, less hierarchical societies performed more effectively in the management of extreme scenarios in the past. However, there are significant systemic differences between pre-modern societies and modern, global democracies; the next section provides evidence that modern democracies are more stable and handle crises better, too.

Planning for and managing disasters and future outcomes

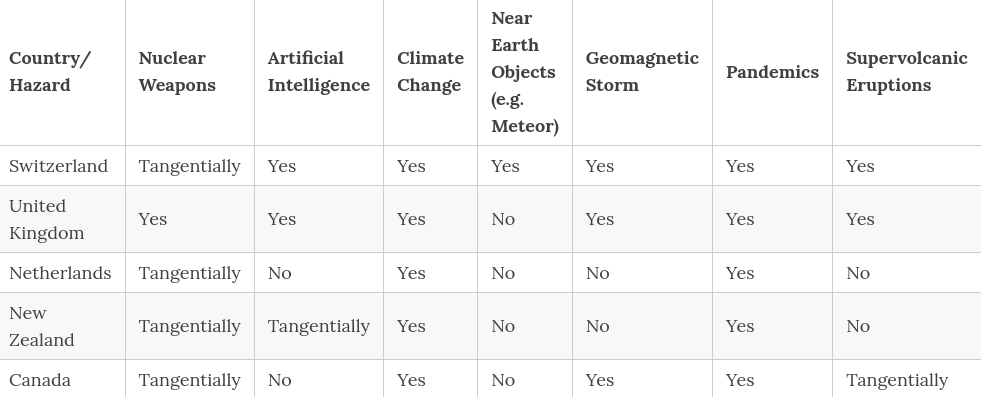

Management and outcomes of disasters are improved by first understanding, and second preparing for them. One proxy used to assess this is the presence and magnitude of national risk assessments; national risk assessments are the attempt by nations to map out the space of possible futures and what dangers might await them there. Countries with strong national risk assessments have, in this sense, made the first step in preparing well for disasters. But not all countries tend to undertake national risk assessments and those which do often differ in their focus. Generally, more democratic governments tend to create better risk assessments than autocratic ones. To compare their farsightedness we can look at how different countries treat global catastrophic risk in their national risk assessments, as these are usually the worst tail risks that can happen (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Overview of what kind of global catastrophes different countries consider in their national risk assessments. “Tangentially” refers to the hazard being mentioned, but not discussed further.

There is evidence that at least some states treat global catastrophic risk as a serious object of national planning, with Switzerland standing out for the breadth and depth of its assessment. The United States is not included in this comparison, as it does not produce a single, consolidated national risk assessment; instead, relevant analyses are distributed across multiple agencies, making them difficult to evaluate as a coherent whole. That said, the United States is distinctive in having produced a risk assessment focused explicitly on global catastrophic risks, with plans for periodic updates on roughly decennial timescales.

All of the countries included in this comparison are democracies, and there appears to be no publicly available national risk assessment of comparable scope produced by an autocratic government. This does not imply that such assessments do not exist in classified form, but this in and of itself is also a problem. National-scale risk assessment is inherently complex, and important pathways to catastrophe are easily overlooked. Public availability allows external scrutiny and iterative improvement. New Zealand provides a useful illustration: earlier versions of its national risk assessment were classified, but the decision to publish a subsequent iteration exposed the document to substantial criticism, which in turn informed revisions and strengthened overall resilience (Boyd & Wilson, 2021).

Beyond ex ante planning, it is also instructive to examine state performance once disasters actually occur. Lin (2015) provides a systematic analysis of this question, examining 150 countries between 1995 and 2009, including their state capacity, how democratic they were and how they responded to disasters. The latter was measured by using publicly available data on how many people were affected by a disaster (death, injury or homelessness). Government expenditure divided by GDP was used as a proxy for state capacity and democratic status was assessed by using the Polity IV dataset. The central finding is that disaster impacts are substantially lower in countries that combine democratic governance with high state capacity. Neither democracy nor capacity alone is sufficient: autocratic systems, as well as democracies with weak state capacity, experience significantly worse outcomes when disasters strike. Lin (2015) attributes this effect in part to democratic accountability, which increases political costs for leaders who fail to manage disaster response effectively, while emphasizing that accountability must be matched by administrative and fiscal capacity to translate into effective action.

When it comes to prevention, there is also evidence that more democratic processes tend to create more forward-looking outcomes. Citizens’s Assemblies aim to bring together a large number of citizens, who are a representative sample of their society. These are provided information and time to create a broad perspective and suitable solutions for societal problems. Lage et al. (2023) examine the outcomes of such assemblies in the European Union in the context of climate policy, finding that their recommendations were consistently more ambitious than those advanced by national governments and more closely aligned with what climate science suggests is required. Because these recommendations emerge from structured deliberation by ordinary citizens rather than political elites, they often command higher levels of public legitimacy. The citizens’ assemblies held in Ireland on abortion provide a well-documented illustration: their recommendations extended well beyond what had previously been considered electorally feasible, yet ultimately received broad public support once the deliberative process underpinning them was widely understood. In short, democracies tend towards high disaster-preparedness, and both their governments and civil societies tend to take steps to understand and reinforce against disasters.

Democracies tend to avoid very bad outcomes

These studies suggest that democracies perform better both in preparing for disasters and in managing them once they occur, provided they possess sufficient state capacity. In addition, there is evidence that democratic systems are also more effective at avoiding severe negative outcomes in the first place.

Democracies rarely go to war against each other: There are very few cases in history where democratic states fought each other. When the analysis is limited to full liberal democracies under contemporary definitions, this number effectively falls to zero. While there is no single, definitive theory explaining this pattern, a prominent explanation (Democratic Peace Theory) runs that it is politically difficult to justify aggression against another fully democratic state to a domestic electorate (Reiter, 2017; Tomz & Weeks, 2013).

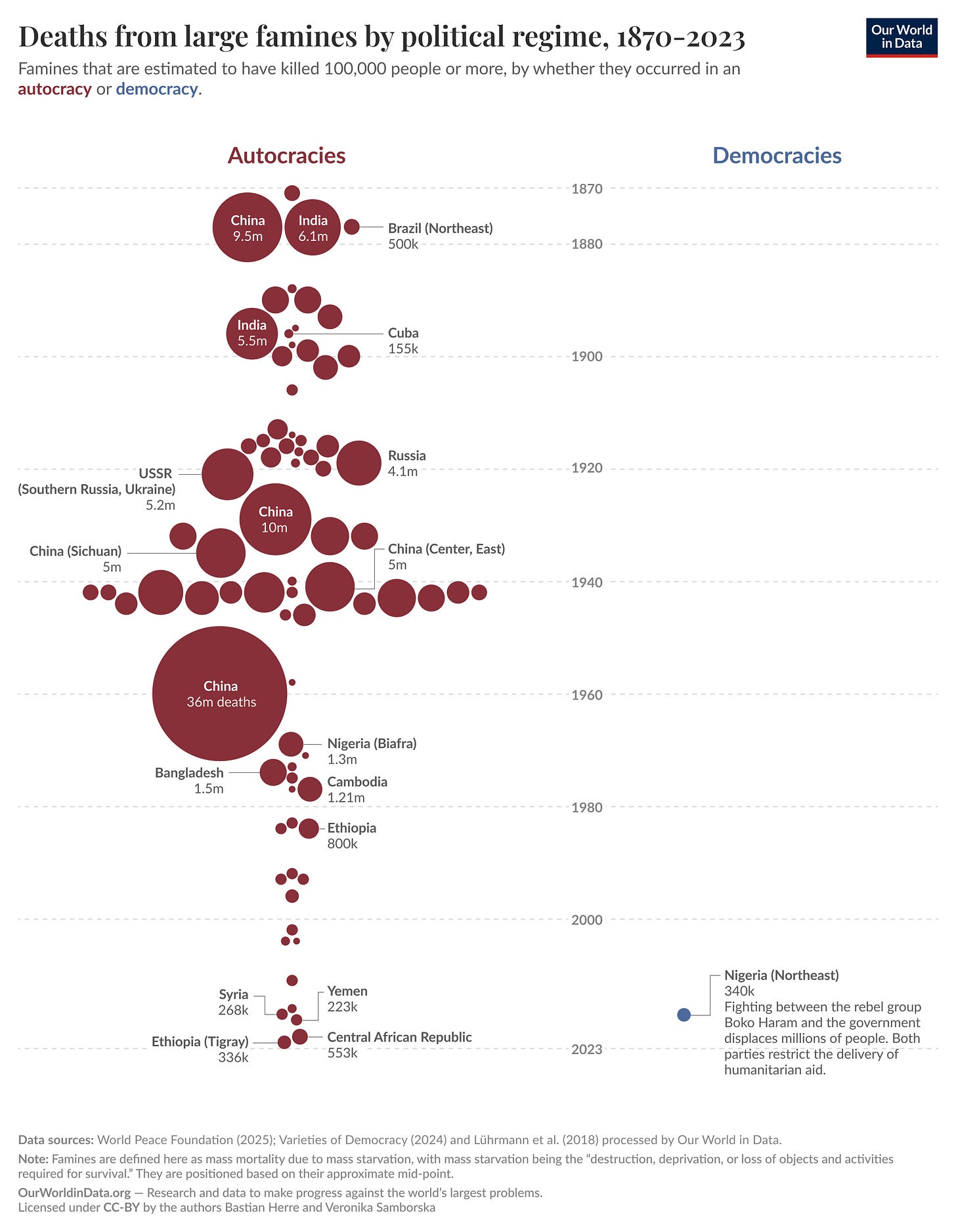

Stable democracies very rarely have famines: Historically, famines have been among the most destructive events societies can face, often resulting in mass mortality and political instability by undermining the most basic conditions for survival. Democracies, however, display a markedly stronger record in this regard. Outcomes depend in part on how both famine and democracy are defined, but according to (Hasell & Roser, 2013), only a single famine has occurred in a democratic state since 1870, whereas autocratic regimes experienced dozens over the same period (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Death from large famines compared by political regime.

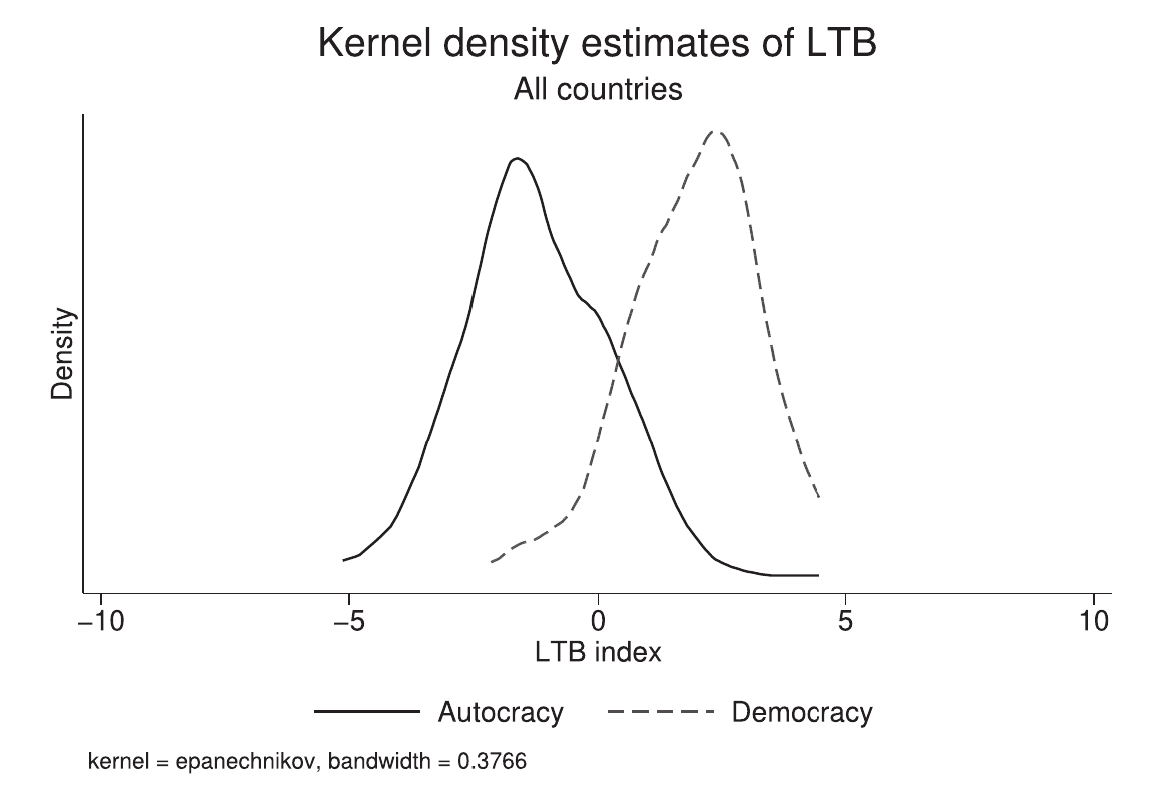

Democracies avoid economic growth for its own sake: There is a persistent argument that autocratic systems are better at long-term planning than democracies, on the grounds that they are not constrained by electoral cycles of four to five years. This claim is examined by Millemaci et al. (2024). They assess the relationship between regime type, economic growth, and longer-term societal outcomes - such as education, health, public transport provision, and responsiveness to public preferences - comparing democracies and autocracies across these dimensions. Their findings indicate that democracies perform at least as well as autocracies in terms of economic growth on average, while the most extreme outcomes at both ends of the distribution - very high growth and severe contraction - are observed in autocratic systems. When societal outcomes are considered, the contrast is even clearer. Democratic countries deliver systematically better outcomes for their populations on these measures (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Comparison of positive societal outcomes (Long-term Background - LTB - index consisting of factors like health, public transport etc.) between democracies and autocracies. A higher index indicates better outcomes for general society. The y axis is a kernel density estimate, this means it is a smoothed approximation of the data points present. In simpler terms this just means higher values on the y-axis indicate more countries are concentrated around that LTB index value.

Democracies often reverse autocratization: It has been established that democracies tend to avoid negative outcomes better and more reliably than autocracies. Accordingly, democratic backsliding into autocracy constitutes a negative outcome in its own right. At the same time, democratic systems also exhibit a degree of self-stabilization in response to autocratic erosion. This dynamic is examined by Nord et al. (2025), who analyzed the evolution of democratic regimes between 1900 and 2023, tracing changes in democratic quality over time. Within this time series, the authors identify episodes in which countries experienced abrupt shifts toward either greater democratization or increased authoritarianism. They find that approximately half of all episodes of autocratization are reversed within a relatively short period, defined in this study as no more than five years. This pattern has strengthened over time, with contemporary democracies reversing autocratizing trends in approximately 73% of cases.

What threatens democracies today?

The reasons for the contemporary decline in democracy are likely numerous and complex (see Figure 1). A review by Loughlin (2019) characterizes this decline as a slow and often opaque process. Rather than occurring through overt coups, democratic erosion today typically proceeds through the gradual degradation of democratic institutions and practices. Hungary provides a frequently cited example; although formally classified as a democracy, the government under Viktor Orbán has, over time, dismantled institutional checks and balances and reshaped the electoral system in ways that substantially reduce the likelihood of electoral defeat. Comparable dynamics can be observed in other established democracies: Examples often cited include the Alternative für Deutschland in Germany and the MAGA movement associated with Donald Trump in the United States. While the mechanisms of democratic erosion are increasingly well documented, the reasons for their apparent acceleration in the present period remain less clear.

Loughlin identifies several contributing factors:

Globalization: Rising globalization has reduced states’ capacity to regulate their domestic economies, as they are increasingly exposed to external forces beyond their direct control. This constrains important avenues for national self-determination.

Inequality: Economic inequality has increased in many countries over recent decades, worsening material conditions for significant segments of the population in democratic societies. This has eroded trust in traditional democratic processes, which had promised broad-based improvements in living standards.

Focus on the individual: Neoliberal capitalism, the dominant economic model across most democracies, places a strong emphasis on individual autonomy. In combination with rising migration and inequality, this emphasis can weaken social cohesion and collective identification. Such collective identification, however, is often important for sustaining democratic legitimacy, particularly when democratic outcomes do not align perfectly with individual preferences.

Economic power of companies: Large multinational corporations, such as Amazon or Apple, exert growing influence over public policy through lobbying and related mechanisms. This can generate voter frustration when political decisions appear to reflect corporate interests rather than popular preferences.

While these are significant claims, they are frequently echoed in other papers examining the relationship between societal conditions, inequality, and democracy. For instance, Centeno & Cohen (2012) discuss neoliberalism’s history and emphasize similar issues as Loughlin. In the late 20th century, neoliberalism emerged as an attractive ideology promising both democracy and prosperity through free markets. As Centeno & Cohen (2012) note, this was especially compelling in the 1990s when the success of the “Asian Tigers” seemed to demonstrate how global market mechanisms could lift countries out of poverty. The apparent triumph of capitalism over the Soviet model further cemented the appeal of neoliberal ideas.

The core tenets were straightforward: Minimize government intervention, privatize public services, and deregulate markets. The theory was that this would maximize economic freedom which would, in turn, guarantee political freedom. This “indivisibility thesis” - the idea that economic and political freedom were inseparable - became deeply influential in policy circles.

However, the implementation of neoliberal policies had several consequences that increased societal vulnerability:

Increased Inequality: The focus on deregulation and tax reduction, particularly for the wealthy, has led to growing inequality.

Weakened State Capacity: Through extensive privatization and deregulation, states reduced their ability to respond to crises and provide public goods.

Broken Feedback Loops: As wealth and power became more concentrated, decision-makers became increasingly insulated from the consequences of their choices, as they mainly hear what needs to be done from lobbyists. This has made it harder for societies to recognize and respond to emerging threats.

A more concrete example of how economic power enables large companies to influence the political system is provided by Supran et al. (2023). They examined ExxonMobil’s company records, showing the company knew by the early 1980s how much fossil fuels would heat the planet. These models accurately predicted recent decades’ warming. Despite this, ExxonMobil used its influence to spread misinformation that contradicted their findings and to persuade policymakers to avoid legislation that would impede their business.

Taken together, these factors share a common underlying feature. They can all be understood as consequences of neoliberal capitalism, which prioritizes market mechanisms as the primary mode of societal coordination while seeking to limit the role of the state.

Actionable insights to make democracies stronger again

Taken together, the preceding examples indicate that strong democratic processes are a central component of societal resilience to catastrophic risks. In addition to enhancing crisis preparedness and response, such processes are also associated with higher levels of citizen wellbeing in the present. This raises the question of how democratic systems might be strengthened. Addressing this challenge requires confronting a set of structural weaknesses, notably high inequality, diminished state capacity, and disrupted democratic feedback loops.

Fixing inequality: Giving citizens the resources and time to participate in democracy

Democratic participation is time-intensive. Broadening participation in decision-making can improve the quality of outcomes, but it also requires sufficient space for deliberation. If citizens are to engage more fully in democratic processes, such engagement must be feasible alongside their working lives. In contemporary economies, however, many individuals work long hours. While some do so by choice, for others this is a necessity driven by basic material needs such as housing and subsistence. For the latter group, increasing discretionary time and security is a prerequisite for meaningful democratic participation. One possible approach is a universal basic income (while the interpretation of trials remain contested, they generally point towards better outcomes on an individual level with regard to outcomes on health and time), which could provide individuals with a financial buffer that enables greater civic engagement. More generally, a wide range of policies that reduce economic pressure - such as extended parental leave, improved childcare provision or higher taxes on multinational corporations and inheritance - could serve similar functions.

Fixing weak state capacity: Making people more excited about democracy

Beyond having the time to participate, citizens also require sufficient motivation to engage in democratic processes. This dimension is among the most difficult to influence through policy. Nonetheless, existing research identifies factors that can increase citizens’ engagement with, and confidence in, the political community they inhabit. One such factor is whether the state is perceived as accessible, competent, and reliable. When public services deteriorate - for example, when local facilities close, public transport is unreliable, or libraries lack adequate funding - it becomes difficult for citizens to view the democratic system as effective. Strengthening public provision therefore plays an important role in restoring confidence in democratic governance. Increased state capacity is also directly relevant to catastrophe preparedness, as it underpins the infrastructure and administrative processes required to mitigate and respond to large-scale risks.

Fixing broken feedback loops: Creating the structures and processes which allow more direct participation in democracy

Once citizens have both the time and motivation to participate, appropriate institutional processes and structures are also required to channel this engagement effectively. A wide range of potential institutional responses could contribute to this goal. At the most ambitious end of the spectrum, this would involve a substantial reallocation of political authority toward lower levels of government. Such arrangements have historical precedent in the United States, most notably in the tradition of town halls. During the formative period of the United States, local councils exercised significant authority and provided the democratic authority and foundation for constitutional development, as locally elected representatives participated directly in drafting governing frameworks. Although much of this authority was later consolidated at the state level, this evolution does not imply that decentralization is inherently irreversible. Contemporary examples also exist from which such models could be drawn. Switzerland, for instance, allocates substantial decision-making authority to subnational levels of government. Similarly, the autonomous region of Rojava in northern Syria represents an ongoing experiment in localized and participatory democratic governance.

A more readily implementable solution could be citizens’ assemblies. Such assemblies have demonstrated a capacity to generate forward-looking policy recommendations that also command relatively high levels of public approval. They can be convened across a wide range of policy domains. One timely application would be the governance and regulation of artificial intelligence. It is also conceivable that citizens’ assemblies could be organized on a transnational basis to contribute to forms of global risk assessment, integrating democratic deliberation with efforts to strengthen global resilience. Another potentially effective approach is the use of participatory budgeting, which grants citizens a degree of authority over how local governments allocate public funds. This approach is grounded in the assumption that local populations are often best placed to identify the challenges they face and to prioritize responses accordingly. These approaches could be further strengthened through the use of digital technologies. A growing number of platforms enable accessible and remote forms of democratic deliberation, lowering barriers to participation and coordination (for example Decidim).

Conclusion

Democracies face significant pressure, yet they remain essential both for sustaining high quality of life and for building societies that are resilient to future risks. The policy options outlined here are not intended as an exhaustive set of solutions, but rather as illustrative examples of how democratic systems might be strengthened. Many additional interventions may also prove effective, provided they expand citizens’ time and resources for participation, foster motivation to engage in democratic self-governance, and establish institutional processes that shift meaningful authority toward lower levels of decision-making.

References

Aspen Institute. (2017). Democracy as Self-Correction. Aspen Institute Centre for Enterprise. https://www.aspeninstitutece.org/article/2017/democracy-as-self-correction/

Boyd, M., & Wilson, N. (2021). Anticipatory Governance for Preventing and Mitigating Catastrophic and Existential Risks. Policy Quarterly, 17(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v17i4.7313

Centeno, M. A., & Cohen, J. N. (2012). The Arc of Neoliberalism. Annual Review of Sociology, 38(Volume 38, 2012), 317–340. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150235

Hasell, J., & Roser, M. (2013). Famines. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/famines

Hoyer, D., Bennett, J. S., Whitehouse, H., François, P., Feeney, K., Levine, J., Reddish, J., Davis, D., & Turchin, P. (2024). CRISES AVERTED How A Few Past Societies Found Adaptive Reforms in the Face of Structural- Demographic Crises. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/hyj48

Hoyer, D., Holder, S., Bennett, J. S., Francois, P., Whitehouse, H., Covey, R. A., Feinman, G., Korotayev, A., Ustyuzhanin, V., Preiser-Kapeller, J., Bard, K., Levine, J., Reddish, J., Orlandi, G., Ainsworth, R., & Turchin, P. (2025). All Crises are Unhappy in Their Own Way: The Role of Societal Instability in Shaping the Past. Social Science History, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2025.10113

Kemp, L. (2025). Goliath’s Curse: The History and Future of Societal Collapse. Viking.

Lage, J., Thema, J., Zell-Ziegler, C., Best, B., Cordroch, L., & Wiese, F. (2023). Citizens call for sufficiency and regulation—A comparison of European citizen assemblies and National Energy and Climate Plans. Energy Research & Social Science, 104, 103254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103254

Lin, T.-H. (2015). Governing Natural Disasters: State Capacity, Democracy, and Human Vulnerability. Social Forces, 93(3), 1267–1300.

Loughlin, M. (2019). The Contemporary Crisis of Constitutional Democracy†. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 39(2), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqz005

Lührmann, A., Tannenberg, M., & Lindberg, S. I. (2018). Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes. Politics and Governance, 6(1), 60–77.

Mathieu, E., Ritchie, H., Rodés-Guirao, L., Appel, C., Gavrilov, D., Giattino, C., Hasell, J., Macdonald, B., Dattani, S., Beltekian, D., Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2020). Excess mortality during the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/excess-mortality-covid

Millemaci, E., Monteforte, F., & Temple, J. R. W. (2024). Have Autocrats Governed for the Long Term? Kyklos. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12425

Nord, M., Angiolillo, F., Lundstedt, M., Wiebrecht, F., & Lindberg, S. I. (2025). When autocratization is reversed: Episodes of U-Turns since 1900. Democratization, 0(0), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2024.2448742

Our World in Data. (2025). Countries that are democracies and autocracies. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/countries-democracies-autocracies-row

Peregrine, P. N. (2018). Social Resilience to Climate-Related Disasters in Ancient Societies: A Test of Two Hypotheses. Weather, Climate, and Society, 10(1), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-17-0052.1

Peregrine, P. N. (2021). Social resilience to nuclear winter: Lessons from the Late Antique Little Ice Age. Global Security: Health, Science and Policy, 6(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/23779497.2021.1963808

Reiter, D. (2017). Is Democracy a Cause of Peace? In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.287

Supran, G., Rahmstorf, S., & Oreskes, N. (2023). Assessing ExxonMobil’s global warming projections. Science, 379(6628), eabk0063. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk0063

Tomz, M. R., & Weeks, J. L. P. (2013). Public Opinion and the Democratic Peace. American Political Science Review, 107(4), 849–865. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000488

Zhang, M., Liu, B., Xiang, G., Yan, X., Ling, Y., & Zuo, C. (2024). Navigating the shift: Understanding public trust in authorities amidst policy shifts in China’s COVID-19 response. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1716. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04224-6